A short documentary was filmed about last year's mental health rally by Brave New Films! It was an amazing experience.

Check out the video. ⤵

WELCOME TO

Discover Monthly Archive

eating disorders

What are Eating Disorders?

According to the APA

Eating disorders are illnesses in which the people experience severe disturbances in their eating behaviors and related thoughts and emotions. People with eating disorders typically become pre-occupied with food and their body weight.

General Statistics

National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders

-

At least 30 million people of all ages and genders suffer from an eating disorder in the U.S.

-

Every 62 minutes at least one person dies as a direct result from an eating disorder.

-

Eating disorders have the highest mortality rate of any mental illness.

-

13% of women over 50 engage in eating disorder behaviors.

-

In a large national study of college students, 3.5% sexual minority women and 2.1% of sexual minority men reported having an eating disorder.

-

16% of transgender college students reported having an eating disorder.

-

In a study following active duty military personnel over time, 5.5% of women and 4% of men had an eating disorder at the beginning of the study, and within just a few years of continued service, 3.3% more women and 2.6% more men developed an eating disorder.

-

Eating disorders affect all races and ethnic groups.

-

Genetics, environmental factors, and personality traits all combine to create risk for an eating disorder.

Anorexia nervosa - causes, symptoms, diagnosis, treatment & pathology

What is anorexia nervosa? Anorexia nervosa is a type of eating disorder in which somebody becomes obsessed with what they eat, and leads to abnormally low body weight.

ARTICLES ABOUT EATING DISORDERS

How Travel Has Shaped My Eating Disorder Recovery

"As we approach the first summer in five years that my feet may not stray from the pathways that have become my mundane, I question what it is to travel with an eating disorder.

For this writing, I approach travel as the voluntary act of temporarily being within, outside of and between any given space or place. I travel from a degree of privilege, of freewill and of leisure.

Wherever I travel, my eating disorder is there with me."

Opinion: How to survive the holidays with an eating disorder

"’Tis the season of robust turkey and latkes and decadent mashed potatoes, of chocolate truffles and cherry glaze and Grandma’s famous pumpkin pie. It’s a time of gathering around a dinner table decorated in miles and miles of red tablecloth and festive centerpieces. It’s a time of saying grace, giving joy, and indulging in homemade food as a family.

Yet, for millions across America, this joyful season quickly is an anxiety-ridden nightmare. For millions across America who have eating disorders, the holiday season is their greatest fear."

Eating Disorders: More than skin deep

"Earlier this month, Mary Cain, one of the most heralded middle distance runners of the 21st century, shared a shocking revelation. In a New York Times video op-ed, Cain detailed years of alleged abuse at the hands of Nike Oregon Project Coach Alberto Salazar. One constant aspect of this abuse was a reported fixation on Cain’s weight, with the athlete reporting that she was shamed in front of teammates for any perceived fluctuation from a specific measurement. Beyond the psychological trauma this pattern of abuse produced, Cain noted the cessation of her menstrual cycle, along with a series of bone fractures, which left her unable to compete. And while Cain’s story is certainly illuminating in what it tells us about eating disorders, it is hardly unique."

THE CHEMISTRY

BEHIND

EATING DISORDERS

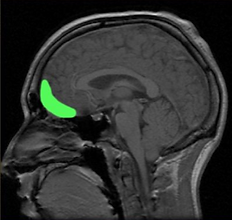

Orbitofrontal Cortex

Problems in dealing with “rewards”

Among people with eating disorders, something goes askew in a region of the brain known as the reward center. This part of the brain processes the good feelings that can come when we get smiles, gifts or compliments. When we receive such a reward, our brain releases dopamine. No wonder it’s often called the ‘feel-good’ chemical. But pathways carrying that signal seem to be miswired in people with eating disorders, studies show.

When it comes to dopamine and serotonin — and even other chemical messengers in the brain, Lock says: “They’re all interacting.” So you can’t fully separate out the effects of each. It’s not like they are “on separate railroad tracks,” moving about the brain individually, he explains.Research shows that people with anorexia also tend to be extra sensitive to rewards. “They get overwhelmed by what the rest of us would find to be an OK stimulus,” says Lock. Even just the basic process of eating can be overwhelming and can trigger anxiety, he says.

What’s worse, studies suggest that people with anorexia become more sensitive to the rewards they receive when they restrict how much they eat, says Guido Frank. He’s a brain researcher in Denver who specializes in eating disorders. Frank is based at the Children’s Hospital Colorado.

Chronically starving the body actually changes the way the brain processes rewards in people with anorexia. He says that makes it even harder for them to eat normally again.

In contrast, people with bulimia seem to be under-stimulated by rewards.

The orbitofrontal cortex, highlighted in green in this head scan, is a structure at the front of the brain. Studies have found differences in this part of the brain in people with eating disorders.

Brain differences

The size and shape of certain brain regions are different in people with eating disorders. Frank led two 2013 studies that illustrate this. Both showed important structural differences in certain brain regions.

Take the orbitofrontal cortex. This brain region sits just between the eyes. It is larger than normal in young people and adults with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Study participants who had recovered from anorexia showed this same enlargement.

This may be an important clue: The affected region includes a structure called the gyrus rectus (JY-rus REK-tus). It plays an important role in regulating how much we eat.

Frank and his fellow researchers found that a second structure, the right insula, also was enlarged in patients with anorexia and in people who had recovered from the illness. In patients with bulimia, the left insula was larger than in healthy people.

The left and right insula are tucked deep inside the brain. The insula tell us what taste we just experienced. It then connects with other brain regions to allow us to feel pleasure or dislike about that taste. Now we can make a decision whether we want more of a particular food, says Frank. The insula also integrates how we feel about our body and our sensation of pain.

Whether these altered regions help trigger eating disorders or instead are caused by them remains unknown, Frank says.

But the new studies do show that these illnesses have a strong basis in brain biology, he says. And those biological origins of eating disorders may occur early in brain development.

These data can help “people to understand what these kids and their families are up against,” Frank says. “It’s not ‘just the fear of weight gain’ and ‘just the fear of getting fat,’” he says. “It’s also something clearly biological that makes it really hard for them to go back to normal.”

HOW DOES TREATMENT HELP?

"Eating disorder treatment depends on your particular disorder and your symptoms. It typically includes a combination of psychological therapy (psychotherapy), nutrition education, medical monitoring and sometimes medications.

Eating disorder treatment also involves addressing other health problems caused by an eating disorder, which can be serious or even life-threatening if they go untreated for too long. If an eating disorder doesn't improve with standard treatment or causes health problems, you may need hospitalization or another type of inpatient program.

Having an organized approach to eating disorder treatment can help you manage symptoms, return to a healthy weight, and maintain your physical and mental health.

Where to start

Whether you start by seeing your primary care practitioner or some type of mental health professional, you'll likely benefit from a referral to a team of professionals who specialize in eating disorder treatment. Members of your treatment team may include:

-

A mental health professional, such as a psychologist to provide psychological therapy. If you need medication prescription and management, you may see a psychiatrist. Some psychiatrists also provide psychological therapy.

-

A registered dietitian to provide education on nutrition and meal planning.

-

Medical or dental specialists to treat health or dental problems that result from your eating disorder.

-

Your partner, parents or other family members. For young people still living at home, parents should be actively involved in treatment and may supervise meals.

It's best if everyone involved in your treatment communicates about your progress so that adjustments can be made to treatment as needed.

Managing an eating disorder can be a long-term challenge. You may need to continue to see members of your treatment team on a regular basis, even if your eating disorder and related health problems are under control.

Setting up a treatment plan

You and your treatment team determine what your needs are and come up with goals and guidelines. Your treatment team works with you to:

-

Develop a treatment plan. This includes a plan for treating your eating disorder and setting treatment goals. It also makes it clear what to do if you're not able to stick with your plan.

-

Treat physical complications. Your treatment team monitors and addresses any health and medical issues that are a result of your eating disorder.

-

Identify resources. Your treatment team can help you discover what resources are available in your area to help you meet your goals.

-

Work to identify affordable treatment options. Hospitalization and outpatient programs for treating eating disorders can be expensive, and insurance may not cover all the costs of your care. Talk with your treatment team about financial issues and any concerns — don't avoid treatment because of the potential cost.

Psychological therapy

Psychological therapy is the most important component of eating disorder treatment. It involves seeing a psychologist or another mental health professional on a regular basis.

Therapy may last from a few months to years. It can help you to:

-

Normalize your eating patterns and achieve a healthy weight

-

Exchange unhealthy habits for healthy ones

-

Learn how to monitor your eating and your moods

-

Develop problem-solving skills

-

Explore healthy ways to cope with stressful situations

-

Improve your relationships

-

Improve your mood

Treatment may involve a combination of different types of therapy, such as:

-

Cognitive behavioral therapy. This type of psychotherapy focuses on behaviors, thoughts and feelings related to your eating disorder. After helping you gain healthy eating behaviors, it helps you learn to recognize and change distorted thoughts that lead to eating disorder behaviors.

-

Family-based therapy. During this therapy, family members learn to help you restore healthy eating patterns and achieve a healthy weight until you can do it on your own. This type of therapy can be especially useful for parents learning how to help a teen with an eating disorder.

-

Group cognitive behavioral therapy. This type of therapy involves meeting with a psychologist or other mental health professional along with others who are diagnosed with an eating disorder. It can help you address thoughts, feelings and behaviors related to your eating disorder, learn skills to manage symptoms, and regain healthy eating patterns.

Your psychologist or other mental health professional may ask you to do homework, such as keep a food journal to review in therapy sessions and identify triggers that cause you to binge, purge or do other unhealthy eating behaviors.

Nutrition education

Registered dietitians and other professionals involved in your treatment can help you better understand your eating disorder and help you develop a plan to achieve and maintain healthy eating habits. Goals of nutrition education may be to:

-

Work toward a healthy weight

-

Understand how nutrition affects your body, including recognizing how your eating disorder causes nutrition issues and physical problems

-

Practice meal planning

-

Establish regular eating patterns — generally, three meals a day with regular snacks

-

Take steps to avoid dieting or bingeing

-

Correct health problems that are a result of malnutrition or obesity

Medications for eating disorders

Medications can't cure an eating disorder. They're most effective when combined with psychological therapy.

Antidepressants are the most common medications used to treat eating disorders that involve binge-eating or purging behaviors, but depending on the situation, other medications are sometimes prescribed.

Taking an antidepressant may be especially helpful if you have bulimia or binge-eating disorder. Antidepressants can also help reduce symptoms of depression or anxiety, which frequently occur along with eating disorders.

You may also need to take medications for physical health problems caused by your eating disorder.

Hospitalization for eating disorders

Hospitalization may be necessary if you have serious physical or mental health problems or if you have anorexia and are unable to eat or gain weight. Severe or life-threatening physical health problems that occur with anorexia can be a medical emergency.

In many cases, the most important goal of hospitalization is to stabilize acute medical symptoms through beginning the process of normalizing eating and weight. The majority of eating and weight restoration takes place in the outpatient setting.

Hospital day treatment programs

Day treatment programs are structured and generally require attendance for multiple hours a day, several days a week. Day treatment can include medical care; group, individual and family therapy; structured eating sessions; and nutrition education.

Residential treatment for eating disorders

With residential treatment, you temporarily live at an eating disorder treatment facility. A residential treatment program may be necessary if you need long-term care for your eating disorder or you've been in the hospital a number of times but your mental or physical health hasn't improved.

Ongoing treatment for health problems

Eating disorders can cause serious health problems related to inadequate nutrition, overeating, bingeing and other factors. The type of health problems caused by eating disorders depends on the type and severity of the eating disorder. In many cases, problems caused by an eating disorder require ongoing treatment and monitoring.

Health problems linked to eating disorders may include:

-

Electrolyte imbalances, which can interfere with the functioning of your muscles, heart and nerves

-

Heart problems and high blood pressure

-

Digestive problems

-

Nutrient deficiencies

-

Dental cavities and erosion of the surface of your teeth from frequent vomiting (bulimia)

-

Low bone density (osteoporosis) as a result of irregular or absent menstruation or long-term malnutrition (anorexia)

-

Stunted growth caused by poor nutrition (anorexia)

-

Mental health conditions such as depression, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder or substance abuse

-

Lack of menstruation and problems with infertility and pregnancy

Take an active role

You are the most important member of your treatment team. For successful treatment, you need to be actively involved in your treatment and so do your family members and other loved ones. Your treatment team can provide education and tell you where to find more information and support.

There's a lot of misinformation about eating disorders on the web, so follow your treatment team's advice and get suggestions on reputable websites to learn more about your eating disorder. Examples of helpful websites include the National Eating Disorders Association (NEDA), as well as Families Empowered and Supporting Treatment of Eating Disorders (F.E.A.S.T.).

BOOKS THAT EFFECTIVELY PORTRAY EATING DISORDERS

the art of starving

by Sam J. Miller

Overview

"Matt hasn’t eaten in days.

His stomach stabs and twists inside, pleading for a meal. But Matt won’t give in. The hunger clears his mind, keeps him sharp—and he needs to be as sharp as possible if he’s going to find out just how Tariq and his band of high school bullies drove his sister, Maya, away.

Matt’s hardworking mom keeps the kitchen crammed with food, but Matt can resist the siren call of casseroles and cookies because he has discovered something: the less he eats the more he seems to have . . . powers. The ability to see things he shouldn’t be able to see. The knack of tuning in to thoughts right out of people’s heads. Maybe even the authority to bend time and space.

A darkly funny, moving story of body image, addiction, friendship, and love, Sam J. Miller’s debut novel will resonate with any reader who’s ever craved the power that comes with self-acceptance."

not all black girls know how to eat: a story of bulimia

by Stephanie Covington Armstrong

Overview

"Stephanie Covington Armstrong does not fit the stereotype of a woman with an eating disorder. She grew up poor and hungry in the inner city. Foster care, sexual abuse, and overwhelming insecurity defined her early years. But the biggest difference is her race: Stephanie is black.

In this moving first-person narrative, Armstrong describes her struggle as a black woman with a disorder consistently portrayed as a white woman’s problem. Trying to escape her selfhatred and her food obsession by never slowing down, Stephanie becomes trapped in a downward spiral. Finally, she can no longer deny that she will die if she doesn’t get help, overcome her shame, and conquer her addiction to using food as a weapon against herself."

CELEBRITIES WHO ADVOCATE

"'I didn’t know if I was going to feel comfortable with talking about body image and talking about the stuff I’ve gone through in terms of how unhealthy that’s been for me — my relationship with food and all that over the years,' she tells Variety. 'But the way that Lana (Wilson, the film’s director) tells the story, it really makes sense. I’m not as articulate as I should be about this topic because there are so many people who could talk about it in a better way. But all I know is my own experience. And my relationship with food was exactly the same psychology that I applied to everything else in my life: If I was given a pat on the head, I registered that as good. If I was given a punishment, I registered that as bad.'"

"From early adolescence Brand was suspected to be bipolar and hyper-manic, though he was only treated for depression. Around the age of 11 he started binge-eating and vomiting. 'It was really unusual in boys, quite embarrassing. But I found it euphoric.'

As an adult, when he was in rehab, the bulimia briefly returned. 'It was clearly about getting out of myself and isolation. Feeling inadequate and unpleasant.'

It didn't help that Brand was a lonely only child, and fat. 'I didn't master the bulimia, obviously.' Seriously, does he feel sorry for the child he was? 'I've realised that I do,' he says. 'Of course I've been through lots of therapy. But I do feel a sense of "you poor little sod". I loved my mum madly, but I had a lot of prohibiting, inhibiting things around. My feeling about my childhood was that it was lonely and difficult.'"