A short documentary was filmed about last year's mental health rally by Brave New Films! It was an amazing experience.

Check out the video. ⤵

WELCOME TO

Discover Monthly Archive

What is Bipolar Disorder?

According to the NIMH

General Statistics

Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance

-

Bipolar disorder is more likely to affect the children of parents who have the disorder. When one parent has bipolar disorder, the risk to each child is l5 to 30%. When both parents have bipolar disorder, the risk increases to 50 to 75%. (National Institute of Mental Health)

-

Bipolar Disorder may be at least as common among youth as among adults. In a recent NIMH study, one percent of adolescents ages 14 to 18 were found to have met criteria for bipolar disorder or cyclothymia in their lifetime. (National Institute of Mental Health)

-

Some 20% of adolescents with major depression develop bipolar disorder within five years of the onset of depression. (Birmaher, B., “Childhood and Adolescent Depression: A Review of the Past 10 Years.” Part I, 1995)

-

Up to one-third of the 3.4 million children and adolescents with depression in the United States may actually be experiencing the early onset of bipolar disorder. (American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 1997)

-

When manic, children and adolescents, in contrast to adults, are more likely to be irritable and prone to destructive outbursts than to be elated or euphoric. When depressed, there may be many physical complaints such as headaches, and stomachaches or tiredness; poor performance in school, irritability, social isolation, and extreme sensitivity to rejection or failure. (National Institute of Mental Health).

Tell Me About Bipolar Disorder

ARTICLES ABOUT BIPOLAR DISORDER

What It’s Like To Go Through A Depressive Episode When You Have Bipolar Disorder

"It’s been about a decade since I was first diagnosed with bipolar disorder — bipolar II to be exact — a type of mental illness characterized by cycling between mania and depression. And yet the arrival of a cycle still manages to catch me off guard. The sudden onset of a new depressive cycle forces me to scramble into what I call “survival mode.” It's a state of mind I use to protect myself, to disassociate from the negative energy trying to consume me. While using breathing techniques, I imagine I am somewhere else, somewhere quiet. I constantly repeat to myself, “Survive today. Tomorrow will be different.”"

‘I just thought I was broken’: How UT student copes with bipolar diagnosis

"“I just thought I was broken. I just thought there was something wrong,” said Garza, an advertising junior. “It was just so relieving to finally feel like … my life doesn’t have to be like this forever’... I can be, quote unquote, normal.”

Bipolar disorder is a chronic mental illness characterized by extreme highs and lows in mood behavior known as episodes of mania or depression, according to the National Institute of Mental Health. These periods can last weeks, months or even years at a time."

THE CHEMISTRY

BEHIND

BIPOLAR DISORDER

The brain uses a number of chemicals as messengers to communicate with other parts of the brain and nervous system. These chemical messengers, known as neurotransmitters, are essential to all of the brain's functions. Since they are messengers, they typically come from one place and go to another to deliver their messages. Where one neuron or nerve cell ends, another one begins. In between two linked neurons is a tiny space or gap called a synapse. In a simple scenario, one cell sends a neurotransmitter message across this synaptic junction and the next cell receives the signal by catching the messenger chemical as it floats across the synapse in a receptor structure. The receiving neuron's capture of the neurotransmitter chemicals alerts it that a message has been sent, and this neuron in turn sends a new message off to additional neurons that it is connected to, and so on down the line.

Importantly, neurons cannot communicate with each other except by means of this synaptic chemical message. The brain would cease to function in an instant if chemical messengers were somehow removed. By providing a mechanism for allowing neurons to communicate with one another, neurotransmitters literally enable the brain to function. There are millions and millions of individual synapses in the brain. The neurotransmitter traffic and activity occurring inside those synapses is constant and complicated.

There are many different kinds of neurotransmitter chemicals in the brain. The neurotransmitters that are implicated in bipolar illness include dopamine, norepinephrine, serotonin, GABA (gamma-aminobutyrate), glutamate, and acetylcholine. Researchers also suspect that another class of neurotransmitter chemicals known as neuropeptides (including endorphins, somatostatin, vasopressin, and oxytocin) play an important role in both normal and bipolar brains.

Measuring neurotransmitters, their chemical variants, locations, and their effects constitute a large area of study in bipolar research. It is known that these chemicals are in some way unbalanced in the bipolar brain compared to normal brain. For example, GABA is observed to be lower in the blood and spinal fluid of bipolar patients, while oxytocin-active neurons are increased in bipolar patients, but the relevancy of these findings to overall brain functioning in bipolar and normal individuals is not yet understood. Whether the presence, absence, or change in these chemicals is a cause or outcome of bipolar disorder remains to be determined, but the importance of neurochemicals in creating bipolar disease is indisputable.

HOW DOES TREATMENT HELP?

Recovering from bipolar disorder doesn’t happen overnight. As with the mood swings of bipolar disorder, treatment has its own ups and downs. Finding the right treatments takes time and setbacks happen. But with careful management and a commitment to getting better, you can get your symptoms under control and live life to the fullest.

Medication treatment for bipolar disorder

Most people with bipolar disorder need medication in order to keep their symptoms under control. When medication is continued on a long-term basis, it can reduce the frequency and severity of bipolar mood episodes, and sometimes prevent them entirely. If you have been diagnosed with bipolar disorder, you and your doctor will work together to find the right drug or combination of drugs for your needs. Because everyone responds to medication differently, you may have to try several different medications before you find one that relieves your symptoms.

Check in frequently with your doctor. It’s important to have regular blood tests to make sure that your medication levels are in the therapeutic range. Getting the dose right is a delicate balancing act. Close monitoring by your doctor will help keep you safe and symptom-free.

Continue taking your medication, even if your mood is stable. Don’t stop taking your medication as soon as you start to feel better. Most people need to take medication long-term in order to avoid relapse.

Don’t expect medication to fix all your problems. Bipolar disorder medication can help reduce the symptoms of mania and depression, but in order to feel your best, it’s important to lead a lifestyle that supports wellness. This includes surrounding yourself with supportive people, getting therapy, and getting plenty of rest.

Be extremely cautious with antidepressants. Research shows that antidepressants are not particularly effective in the treatment of bipolar depression. Furthermore, they can trigger mania or cause rapid cycling between depression and mania in people with bipolar disorder.

The importance of therapy for bipolar disorder

Research indicates that people who take medications for bipolar disorder are more likely to get better faster and stay well if they also receive therapy. Therapy can teach you how to deal with problems your symptoms are causing, including relationship, work, and self-esteem issues. Therapy will also address any other problems you’re struggling with, such as substance abuse or anxiety.

Three types of therapy are especially helpful in the treatment of bipolar disorder:

-

Cognitive-behavioral therapy

-

Interpersonal and social rhythm therapy

-

Family-focused therapy

Cognitive-behavioral therapy

In cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), you examine how your thoughts affect your emotions. You also learn how to change negative thinking patterns and behaviors into more positive ways of responding. For bipolar disorder, the focus is on managing symptoms, avoiding triggers for relapse, and problem-solving.

Interpersonal and social rhythm therapy

Interpersonal therapy focuses on current relationship issues and helps you improve the way you relate to the important people in your life. By addressing and solving interpersonal problems, this type of therapy reduces stress in your life. Since stress is a trigger for bipolar disorder, this relationship-oriented approach can help reduce mood cycling.

Social rhythm therapy is often combined with interpersonal therapy is often combined with social rhythm therapy for the treatment of bipolar disorder. People with bipolar disorder are believed to have overly sensitive biological clocks, the internal timekeepers that regulate circadian rhythms. This clock is easily thrown off by disruptions in your daily pattern of activity, also known as your “social rhythms.” Social rhythm therapy focuses on stabilizing social rhythms such as sleeping, eating, and exercising. When these rhythms are stable, the biological rhythms that regulate mood remain stable too.

Family-focused therapy

Living with a person who has bipolar disorder can be difficult, causing strain in family and marital relationships. Family-focused therapy addresses these issues and works to restore a healthy and supportive home environment. Educating family members about the disease and how to cope with its symptoms is a major component of treatment. Working through problems in the home and improving communication is also a focus of treatment.

Complementary treatments for bipolar disorder

Most alternative treatments for bipolar disorder are really complementary treatments, meaning they should be used in conjunction with medication, therapy, and lifestyle changes. Here are a few of the options that show promise:

Light and dark therapy – Like social rhythm therapy, light and dark therapy focuses on the sensitive biological clock in people with bipolar disorder. This easily disrupted clock throws off sleep-wake cycles, a disturbance that can trigger symptoms of mania and depression. Light and dark therapy regulates these biological rhythms—and thus reduces mood cycling— by carefully managing your exposure to light. The major component of this therapy involves creating an environment of regular darkness by restricting artificial light for ten hours every night.

Mindfulness meditation – Research has shown that mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and meditation help fight and prevent depression, anger, agitation, and anxiety. The mindfulness approach uses meditation, yoga, and breathing exercises to focus awareness on the present moment and break negative thinking patterns.

Acupuncture – Some researchers believe that acupuncture may help people with bipolar disorder by modulating their stress response. Studies on acupuncture for depression have shown a reduction in symptoms, and there is increasing evidence that acupuncture may relieve symptoms of mania also.

Discover ADD/ADHD

BOOKS THAT EFFECTIVELY PORTRAY BIPOLAR DISORDER

little & lion

by Brandy Colbert

Overview

"When Suzette comes home to Los Angeles from her boarding school in New England, she isn't sure if she'll ever want to go back. L.A. is where her friends and family are (along with her crush, Emil). And her stepbrother, Lionel, who has been diagnosed with bipolar disorder, needs her emotional support.

But as she settles into her old life, Suzette finds herself falling for someone new...the same girl her brother is in love with. When Lionel's disorder spirals out of control, Suzette is forced to confront her past mistakes and find a way to help her brother before he hurts himself--or worse."

beautiful bipolar: a book about bipolar disorder

by Danielle Workman

Overview

"Danielle Workman, a once blogger turned author, was faced with what she deemed terminal in her ill mind; a diagnosis of Bipolar Disorder. In this book she details her adventures and her experiences with this mental illness, including the bouts of mania, depression and her current thoughts on living life with it. This is a raw and real collection of truths about Bipolar Disorder, and is a beautiful tell-all novel."

CELEBRITIES WHO ADVOCATE

"Demi was relieved when she finally got the diagnosis. 'I went into treatment and I was able to work with incredible doctors who helped me figure out that I was, in fact, bipolar, she says. 'It was a great feeling to find out that there wasn’t anything wrong with me. I just had a mental illness.'"

“Until recently I lived in denial and isolation and in constant fear someone would expose me,” she says. “It was too heavy a burden to carry and I simply couldn’t do that anymore. I sought and received treatment, I put positive people around me and I got back to doing what I love — writing songs and making music.”

month of march

What is ADHD/ADD?

According to the WebMD

ADHD is a chronic condition marked by persistent inattention, hyperactivity, and sometimes impulsivity. ADHD begins in childhood and often lasts into adulthood. As many as 2 out of every 3 children with ADHD continue to have symptoms as adults.

What is the difference between ADHD / ADD?

According to the ADDITUDE

Traditionally, inattentive symptoms of attention deficit like trouble listening or managing time were diagnosed as "ADD." Hyperactive and impulsive symptoms were associated with the term "ADHD."

Today, there is no ADD vs. ADHD; ADD and ADHD are considered subtypes of the same condition and the same diagnosis.

General Statistics

ADDITUDE: Inside the ADHD Mind

-

In its 2016 study, the CDC found that 3.3 million adolescents ages 12-17 have ever been diagnosed with ADHD.

-

Teens drivers diagnosed with ADHD are more likely to be in a traffic accident, be issued traffic and moving violations, and engage in risky driving behaviors.14

-

Up to 27 percent of adolescents with substance abuse disorder have comorbid ADHD.15

-

Adolescents with ADHD clash with their parents about more issues than do adolescents without ADHD.16

-

Male high-school students with ADHD are more likely to experience problems with attendance, GPA, homework, and more. Male teens with ADHD miss school 3 to 10 percent of the time; are between 2.7 and 8.1 times more likely to drop out of high school; fail 7.5 percent of their courses; and have GPAs five to nine points lower than those of male teens without ADHD.17

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD/ADD) - causes, symptoms & pathology

"What is ADHD? ADHD and ADD are synonymous terms used to describe when a child displays symptoms related to not being able to pay attention or is overly active and impulsive. Find more videos at http://osms.it/more."

ARTICLES ABOUT ADHD / ADD

When I Found the Courage to Seek Accommodations as a University Student With ADHD

"Undergraduate school was hectic with ADHD, as was community college. I am now a graduate student working on two master’s degrees and I finally had the courage to ask for disability accommodations after being turned down at the community college level when I was seeking my associate’s degree.

My fear that I would be turned down for accommodations once I was studying for my bachelor’s degree cost me the ability to graduate with honors. I finished my undergraduate degree with a 3.5 GPA but honors is 3.67 or higher. I fought daily in undergraduate school to focus on my assignments with my ADHD interfering with many of my planned times to do assignments. I still refused to ask for the accommodations I needed so badly."

What ‘Attention’ Is Really Like With ADHD

"Growing up in school, I rarely raised my hand to answer a question. For some reason, everyone seemed to know the right answer but me. My brain would always come up with a correct answer, but it was usually not the answer the teacher was looking for. On the rare occasion when I did raise my hand, the teacher would hear my answer and reply, “I never looked at it that way,” or “that wasn’t the answer I was looking for.” I wasn’t wrong, but I wasn’t right either. No one else seemed to have as much trouble figuring out the right answer, and at the time I found that frustrating and discouraging.

I noticed it happening in conversations as well. I would hear my friends talking about something, so I would bring up a topic that was related. They would all look at me confused because they didn’t see the connection between topics and thought I was just bringing up some random topic for no reason. I would try to explain the connection to my friends on occasion, and we would always end up laughing about how obscure the connection would actually be when I stopped to think about it.

For reasons I did not understand yet, I was an out of the box thinker, whether I wanted to be or not. I learned how to embrace that part of me as best I could, and while I would have preferred to fit in with everyone, I grew adjusted to being “different” and made the best of it."

10 Study Tips for the Student With ADHD

"In high school, I was a D-student. I wasn’t unintelligent, quite the opposite, actually. Many of my teachers told me I was a joy to have in class discussions and once they explained the material in class, I had some pretty great contributions. So, why the low marks? Whenever I had to sit down and study, I would short-circuit. I just couldn’t manage to get through the homework. It drove my family bananas! They knew I could do better! I remember one particular evening my father offered me, I kid you not, $100 to read two chapters of a book due the next day and write the accompanying summaries, and I just couldn’t get through it. Tension headaches, not enough stimulation and low frustration tolerance all added up to me doing the exact amount of work I needed to finish high school in four years and not a single bit more.

When I got to college, however, I went to therapy, I did research on my own, I read books on attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and I tried and failed and learned until I finally discovered a method of studying that worked for me. I went from high school to the first college that would take me, and I was miserable there. But once I figured out how my brain worked, I left, did a year at community college and transferred to a top 100 university!"

THE CHEMISTRY

BEHIND

ADHD / ADD

How Neurotransmitters Work In ADHD Brains

Before I tell you about these special brain chemicals, let me explain a bit about brain anatomy.

There are millions of cells, or neurons, densely packed into various regions of the brain. Each region is responsible for a particular function. Some regions interact with our outside world, interpreting vision, hearing, and other sensory inputs to help us figure out what to do and say. Other regions interact with our internal world — our body — in order to regulate the function of our organs.

For the various regions to do their jobs, they must be linked to one another with extensive “wiring.” Of course, there aren’t really wires in the brain. Rather, there are myriad “pathways,” or neural circuits, that carry information from one brain region to another.

Information is transmitted along these pathways via the action of neurotransmitters (scientists have identified 50 different ones, and there may be as many as 200). Each neuron produces tiny quantities of a specific neurotransmitter, which is released into the microscopic space that exists between neurons (called a synapse), stimulating the next cell in the pathway — and no others.

How does a specific neurotransmitter know precisely which neuron to attach to, when there are so many other neurons nearby? Each neurotransmitter has a unique molecular structure — a “key,” if you will — that is able to attach only to a neuron with the corresponding receptor site, or “lock.” When the key finds the neuron bearing the right lock, the neurotransmitter binds to and stimulates that neuron.

[Self-Test: Could You Have a Working Memory Deficit?]

Neurotransmitter Deficiencies In ADHD Brains

Brain scientists have found that deficiencies in specific neurotransmitters underlie many common disorders, including anxiety, mood disorders, anger-control problems, and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

ADHD was the first disorder found to be the result of a deficiency of a specific neurotransmitter — in this case, norepinephrine — and the first disorder found to respond to medications to correct this underlying deficiency. Like all neurotransmitters, norepinephrine is synthesized within the brain. The basic building block of each norepinephrine molecule is dopa; this tiny molecule is converted into dopamine, which, in turn, is converted into norepinephrine.

A Four-Way Partnership

ADHD seems to involve impaired neurotransmitter activity in four functional regions of the brain:

-

Frontal cortex. This region orchestrates high-level functioning: maintaining attention, organization, and executive function. A deficiency of norepinephrine within this brain region might cause inattention, problems with organization, and/or impaired executive functioning.

-

Limbic system. This region, located deeper in the brain, regulates our emotions. A deficiency in this region might result in restlessness, inattention, or emotional volatility.

-

Basal ganglia. These neural circuits regulate communication within the brain. Information from all regions of the brain enters the basal ganglia, and is then relayed to the correct sites in the brain. A deficiency in the basal ganglia can cause information to “short-circuit,” resulting in inattention or impulsivity.

-

Reticular activating system. This is the major relay system among the many pathways that enter and leave the brain. A deficiency in the RAS can cause inattention, impulsivity, or hyperactivity.

These four regions interact with one another, so a deficiency in one region may cause a problem in one or more of the other regions. ADHD may be the result of problems in one or more of these regions.

HOW DOES TREATMENT HELP?

The symptoms of ADHD (also known as ADD) don’t just impact learning. They can also create difficulties in everyday life with friends and family.

So how is ADHD treated? There are a number of treatments available for ADHD, in addition to medication. Some kids respond best to one kind of treatment. Other kids may do best with a different treatment or combination of treatments. Together with your child’s doctor, you can come up with an ADHD treatment plan that’s tailored to meet your child’s needs.

ADHD Medication

For many kids, medication is key to ADHD management. Experts largely agree that it’s the most effective form of treatment for most kids with ADHD. Medication works well for around 80 percent of the kids who take it, if the type and dosage is carefully tailored to them. But medication may not be right for all kids and families.

There are two main types of medication for ADHD: stimulant and non-stimulant. They work in different ways in the brain to help control ADHD’s key symptoms.

For some kids, ADHD medications can have side effects. These usually go away after a few days. If not, the prescriber will probably suggest trying a different medication to see if that will work better. Or she might recommend changing from a stimulant to a non-stimulant, or vice versa.

It’s fairly common for kids with ADHD to also have anxiety or depression. For these kids, doctors may suggest some additional medication or behavioral treatment.

Watch as an expert talks about the importance of treating ADHD in children, and various ADHD treatment options.

Therapies for ADHD

Kids and families affected by ADHD often find it helpful to work with a mental health professional. It’s important to base the type of therapy you choose on what your child and family need. Here are some options.

Behavior therapy: One of the goals of behavior therapy is to change negative behaviors into positive ones. It often involves using a rewards system at home. This type of therapy is helpful for some kids with ADHD, and is often used along with medication.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT): This is a type of talk therapy. The goal of cognitive behavioral therapy is to get kids to think about their thoughts, feelings and behavior. It’s not specifically for ADHD, but it may be helpful for some kids.

In part, CBT helps kids replace negative thoughts with ones that are more realistic and positive. It also helps kids build self-esteem, which tends to be negatively affected by ADHD.

CBT is effective for treating anxiety and depression. Anxiety and/or depression occur in about 50 percent of people with ADHD.

Social skills groups: For some kids, ADHD symptoms can make it hard to socialize. Kids may talk nonstop or have trouble thinking before they speak. They may also have trouble managing their emotions. Joining a social skills group run by a professional can help kids learn and practice important skills for interacting with others.

Other Non-Medication Treatment Options for ADHD

There are other non-medication treatment options that have some research backing. Research has shown these alternative treatments to be somewhat helpful in relieving ADHD symptoms. These treatments and therapies include exercise, outdoor activities, omega supplements, mindfulness and changes in diet.

There are also alternatives some parents try that aren’t backed by research. These include over-the-counter (OTC) supplements and “train the brain” games. It’s important to know that OTC supplements are not regulated by law.

Support in School for ADHD

There are a number of classroom accommodations that can help kids with ADHD. These include things like getting extended time on tests, being seated at the front of the classroom and having permission to get up and move during class. You can also talk to your child’s teacher about trying informal supports.

A behavior intervention plan (BIP) might be helpful for some kids with ADHD. This plan outlines steps teachers take to stop problem behaviors at school. A BIP also explains how teachers and the school will encourage appropriate behavior.

Ways to Help at Home

There are many strategies you can try to help your child with ADHD at home. Learn about different professionals who help kids with ADHD. And find out what to do if your child was recently diagnosed with ADHD.

BOOKS THAT EFFECTIVELY PORTRAY ADHD / ADD

fish in a tree

by Lynda Mullaly Hunt

Overview

"Ally has been smart enough to fool a lot of smart people. Every time she lands in a new school, she is able to hide her inability to read by creating clever yet disruptive distractions. She is afraid to ask for help; after all, how can you cure dumb? However, her newest teacher Mr. Daniels sees the bright, creative kid underneath the trouble maker. With his help, Ally learns not to be so hard on herself and that dyslexia is nothing to be ashamed of. As her confidence grows, Ally feels free to be herself and the world starts opening up with possibilities. She discovers that there’s a lot more to her—and to everyone—than a label, and that great minds don’t always think alike."

hyper: a personal video history of adhd

by Timothy Denevi

Overview

"The first book of its kind about what it’s like to be a child with ADHD, Hyper is a “haunting narrative that explores the world’s most scrutinized childhood condition from the inside out” (Nature) that also illuminates the history of how we came to medicate more than four million children today.

Among the first generation of boys prescribed medication for ADHD in the 1980s, Timothy Denevi took Ritalin at the age of six and suffered a psychotic reaction. Thus began his long odyssey through a variety of treatments. In Hyper, Denevi describes how he made his way to adulthood, knowing he was a problem for those who loved him, longing to be able to be good and fit in, and finally realizing he had to come to grips with his disorder before his life spun out of control. Using these experiences as a springboard, Denevi also traces our understanding and treatment of ADHD from the nineteenth century, when bad parenting and even government conspiracies were blamed, through the twentieth century and drug treatments like Benzedrine, Ritalin, and antidepressants. His insightful history shows how drugs became the treatment of choice for ADHD, rather than individually crafted treatments like the one that saved his life."

CELEBRITIES WHO ADVOCATE

"'I simply couldn’t sit still, because it was difficult for me to focus on one thing at a time,' Phelps recalls in Beneath the Surface. 'I had to be in the middle of everything.'

That was especially difficult at home. When he was 7, Phelps’ parents divorced. He says, 'As I began to grasp that my dad would be away for a long time, I needed something that could grab my attention.'"

"When it comes to the traditional expectations of a pop star in Hollywood, Solange Knowles shatters the glass ceiling as a woman of color who also happens to be diagnosed with a disability that affects 10 percent of the U.S. population: ADHD. Knowles has been outspoken about her ADHD, educating people about her disability.

'I was diagnosed with ADHD twice,' Knowles said. 'I didn’t believe the first doctor who told me, and I had a whole theory that ADHD was just something they invented to make you pay for medicine, but then the second doctor told me I had it.'"

Discover Eating Disorders

month of february

What are Eating Disorders?

According to the APA

Eating disorders are illnesses in which the people experience severe disturbances in their eating behaviors and related thoughts and emotions. People with eating disorders typically become pre-occupied with food and their body weight.

General Statistics

National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders

-

At least 30 million people of all ages and genders suffer from an eating disorder in the U.S.

-

Every 62 minutes at least one person dies as a direct result from an eating disorder.

-

Eating disorders have the highest mortality rate of any mental illness.

-

13% of women over 50 engage in eating disorder behaviors.

-

In a large national study of college students, 3.5% sexual minority women and 2.1% of sexual minority men reported having an eating disorder.

-

16% of transgender college students reported having an eating disorder.

-

In a study following active duty military personnel over time, 5.5% of women and 4% of men had an eating disorder at the beginning of the study, and within just a few years of continued service, 3.3% more women and 2.6% more men developed an eating disorder.

-

Eating disorders affect all races and ethnic groups.

-

Genetics, environmental factors, and personality traits all combine to create risk for an eating disorder.

Anorexia nervosa - causes, symptoms, diagnosis, treatment & pathology

"What is anorexia nervosa? Anorexia nervosa is a type of eating disorder in which somebody becomes obsessed with what they eat, and leads to abnormally low body weight."

ARTICLES ABOUT EATING DISORDERS

How Travel Has Shaped My Eating Disorder Recovery

"As we approach the first summer in five years that my feet may not stray from the pathways that have become my mundane, I question what it is to travel with an eating disorder.

For this writing, I approach travel as the voluntary act of temporarily being within, outside of and between any given space or place. I travel from a degree of privilege, of freewill and of leisure.

Wherever I travel, my eating disorder is there with me."

Opinion: How to survive the holidays with an eating disorder

"’Tis the season of robust turkey and latkes and decadent mashed potatoes, of chocolate truffles and cherry glaze and Grandma’s famous pumpkin pie. It’s a time of gathering around a dinner table decorated in miles and miles of red tablecloth and festive centerpieces. It’s a time of saying grace, giving joy, and indulging in homemade food as a family.

Yet, for millions across America, this joyful season quickly is an anxiety-ridden nightmare. For millions across America who have eating disorders, the holiday season is their greatest fear."

Eating Disorders: More than skin deep

"Earlier this month, Mary Cain, one of the most heralded middle distance runners of the 21st century, shared a shocking revelation. In a New York Times video op-ed, Cain detailed years of alleged abuse at the hands of Nike Oregon Project Coach Alberto Salazar. One constant aspect of this abuse was a reported fixation on Cain’s weight, with the athlete reporting that she was shamed in front of teammates for any perceived fluctuation from a specific measurement. Beyond the psychological trauma this pattern of abuse produced, Cain noted the cessation of her menstrual cycle, along with a series of bone fractures, which left her unable to compete. And while Cain’s story is certainly illuminating in what it tells us about eating disorders, it is hardly unique."

THE CHEMISTRY

BEHIND

EATING DISORDERS

Orbitofrontal Cortex

Problems in dealing with “rewards”

Among people with eating disorders, something goes askew in a region of the brain known as the reward center. This part of the brain processes the good feelings that can come when we get smiles, gifts or compliments. When we receive such a reward, our brain releases dopamine. No wonder it’s often called the ‘feel-good’ chemical. But pathways carrying that signal seem to be miswired in people with eating disorders, studies show.

When it comes to dopamine and serotonin — and even other chemical messengers in the brain, Lock says: “They’re all interacting.” So you can’t fully separate out the effects of each. It’s not like they are “on separate railroad tracks,” moving about the brain individually, he explains.Research shows that people with anorexia also tend to be extra sensitive to rewards. “They get overwhelmed by what the rest of us would find to be an OK stimulus,” says Lock. Even just the basic process of eating can be overwhelming and can trigger anxiety, he says.

What’s worse, studies suggest that people with anorexia become more sensitive to the rewards they receive when they restrict how much they eat, says Guido Frank. He’s a brain researcher in Denver who specializes in eating disorders. Frank is based at the Children’s Hospital Colorado.

Chronically starving the body actually changes the way the brain processes rewards in people with anorexia. He says that makes it even harder for them to eat normally again.

In contrast, people with bulimia seem to be under-stimulated by rewards.

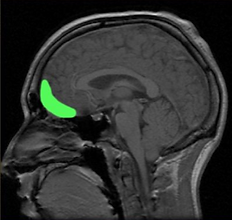

The orbitofrontal cortex, highlighted in green in this head scan, is a structure at the front of the brain. Studies have found differences in this part of the brain in people with eating disorders.

Brain differences

The size and shape of certain brain regions are different in people with eating disorders. Frank led two 2013 studies that illustrate this. Both showed important structural differences in certain brain regions.

Take the orbitofrontal cortex. This brain region sits just between the eyes. It is larger than normal in young people and adults with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Study participants who had recovered from anorexia showed this same enlargement.

This may be an important clue: The affected region includes a structure called the gyrus rectus (JY-rus REK-tus). It plays an important role in regulating how much we eat.

Frank and his fellow researchers found that a second structure, the right insula, also was enlarged in patients with anorexia and in people who had recovered from the illness. In patients with bulimia, the left insula was larger than in healthy people.

The left and right insula are tucked deep inside the brain. The insula tell us what taste we just experienced. It then connects with other brain regions to allow us to feel pleasure or dislike about that taste. Now we can make a decision whether we want more of a particular food, says Frank. The insula also integrates how we feel about our body and our sensation of pain.

Whether these altered regions help trigger eating disorders or instead are caused by them remains unknown, Frank says.

But the new studies do show that these illnesses have a strong basis in brain biology, he says. And those biological origins of eating disorders may occur early in brain development.

These data can help “people to understand what these kids and their families are up against,” Frank says. “It’s not ‘just the fear of weight gain’ and ‘just the fear of getting fat,’” he says. “It’s also something clearly biological that makes it really hard for them to go back to normal.”

HOW DOES TREATMENT HELP?

"Eating disorder treatment depends on your particular disorder and your symptoms. It typically includes a combination of psychological therapy (psychotherapy), nutrition education, medical monitoring and sometimes medications.

Eating disorder treatment also involves addressing other health problems caused by an eating disorder, which can be serious or even life-threatening if they go untreated for too long. If an eating disorder doesn't improve with standard treatment or causes health problems, you may need hospitalization or another type of inpatient program.

Having an organized approach to eating disorder treatment can help you manage symptoms, return to a healthy weight, and maintain your physical and mental health.

Where to start

Whether you start by seeing your primary care practitioner or some type of mental health professional, you'll likely benefit from a referral to a team of professionals who specialize in eating disorder treatment. Members of your treatment team may include:

-

A mental health professional, such as a psychologist to provide psychological therapy. If you need medication prescription and management, you may see a psychiatrist. Some psychiatrists also provide psychological therapy.

-

A registered dietitian to provide education on nutrition and meal planning.

-

Medical or dental specialists to treat health or dental problems that result from your eating disorder.

-

Your partner, parents or other family members. For young people still living at home, parents should be actively involved in treatment and may supervise meals.

It's best if everyone involved in your treatment communicates about your progress so that adjustments can be made to treatment as needed.

Managing an eating disorder can be a long-term challenge. You may need to continue to see members of your treatment team on a regular basis, even if your eating disorder and related health problems are under control.

Setting up a treatment plan

You and your treatment team determine what your needs are and come up with goals and guidelines. Your treatment team works with you to:

-

Develop a treatment plan. This includes a plan for treating your eating disorder and setting treatment goals. It also makes it clear what to do if you're not able to stick with your plan.

-

Treat physical complications. Your treatment team monitors and addresses any health and medical issues that are a result of your eating disorder.

-

Identify resources. Your treatment team can help you discover what resources are available in your area to help you meet your goals.

-

Work to identify affordable treatment options. Hospitalization and outpatient programs for treating eating disorders can be expensive, and insurance may not cover all the costs of your care. Talk with your treatment team about financial issues and any concerns — don't avoid treatment because of the potential cost.

Psychological therapy

Psychological therapy is the most important component of eating disorder treatment. It involves seeing a psychologist or another mental health professional on a regular basis.

Therapy may last from a few months to years. It can help you to:

-

Normalize your eating patterns and achieve a healthy weight

-

Exchange unhealthy habits for healthy ones

-

Learn how to monitor your eating and your moods

-

Develop problem-solving skills

-

Explore healthy ways to cope with stressful situations

-

Improve your relationships

-

Improve your mood

Treatment may involve a combination of different types of therapy, such as:

-

Cognitive behavioral therapy. This type of psychotherapy focuses on behaviors, thoughts and feelings related to your eating disorder. After helping you gain healthy eating behaviors, it helps you learn to recognize and change distorted thoughts that lead to eating disorder behaviors.

-

Family-based therapy. During this therapy, family members learn to help you restore healthy eating patterns and achieve a healthy weight until you can do it on your own. This type of therapy can be especially useful for parents learning how to help a teen with an eating disorder.

-

Group cognitive behavioral therapy. This type of therapy involves meeting with a psychologist or other mental health professional along with others who are diagnosed with an eating disorder. It can help you address thoughts, feelings and behaviors related to your eating disorder, learn skills to manage symptoms, and regain healthy eating patterns.

Your psychologist or other mental health professional may ask you to do homework, such as keep a food journal to review in therapy sessions and identify triggers that cause you to binge, purge or do other unhealthy eating behaviors.

Nutrition education

Registered dietitians and other professionals involved in your treatment can help you better understand your eating disorder and help you develop a plan to achieve and maintain healthy eating habits. Goals of nutrition education may be to:

-

Work toward a healthy weight

-

Understand how nutrition affects your body, including recognizing how your eating disorder causes nutrition issues and physical problems

-

Practice meal planning

-

Establish regular eating patterns — generally, three meals a day with regular snacks

-

Take steps to avoid dieting or bingeing

-

Correct health problems that are a result of malnutrition or obesity

Medications for eating disorders

Medications can't cure an eating disorder. They're most effective when combined with psychological therapy.

Antidepressants are the most common medications used to treat eating disorders that involve binge-eating or purging behaviors, but depending on the situation, other medications are sometimes prescribed.

Taking an antidepressant may be especially helpful if you have bulimia or binge-eating disorder. Antidepressants can also help reduce symptoms of depression or anxiety, which frequently occur along with eating disorders.

You may also need to take medications for physical health problems caused by your eating disorder.

Hospitalization for eating disorders

Hospitalization may be necessary if you have serious physical or mental health problems or if you have anorexia and are unable to eat or gain weight. Severe or life-threatening physical health problems that occur with anorexia can be a medical emergency.

In many cases, the most important goal of hospitalization is to stabilize acute medical symptoms through beginning the process of normalizing eating and weight. The majority of eating and weight restoration takes place in the outpatient setting.

Hospital day treatment programs

Day treatment programs are structured and generally require attendance for multiple hours a day, several days a week. Day treatment can include medical care; group, individual and family therapy; structured eating sessions; and nutrition education.

Residential treatment for eating disorders

With residential treatment, you temporarily live at an eating disorder treatment facility. A residential treatment program may be necessary if you need long-term care for your eating disorder or you've been in the hospital a number of times but your mental or physical health hasn't improved.

Ongoing treatment for health problems

Eating disorders can cause serious health problems related to inadequate nutrition, overeating, bingeing and other factors. The type of health problems caused by eating disorders depends on the type and severity of the eating disorder. In many cases, problems caused by an eating disorder require ongoing treatment and monitoring.

Health problems linked to eating disorders may include:

-

Electrolyte imbalances, which can interfere with the functioning of your muscles, heart and nerves

-

Heart problems and high blood pressure

-

Digestive problems

-

Nutrient deficiencies

-

Dental cavities and erosion of the surface of your teeth from frequent vomiting (bulimia)

-

Low bone density (osteoporosis) as a result of irregular or absent menstruation or long-term malnutrition (anorexia)

-

Stunted growth caused by poor nutrition (anorexia)

-

Mental health conditions such as depression, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder or substance abuse

-

Lack of menstruation and problems with infertility and pregnancy

Take an active role

You are the most important member of your treatment team. For successful treatment, you need to be actively involved in your treatment and so do your family members and other loved ones. Your treatment team can provide education and tell you where to find more information and support.

There's a lot of misinformation about eating disorders on the web, so follow your treatment team's advice and get suggestions on reputable websites to learn more about your eating disorder. Examples of helpful websites include the National Eating Disorders Association (NEDA), as well as Families Empowered and Supporting Treatment of Eating Disorders (F.E.A.S.T.).

BOOKS THAT EFFECTIVELY PORTRAY EATING DISORDERS

the art of starving

by Sam J. Miller

Overview

"Matt hasn’t eaten in days.

His stomach stabs and twists inside, pleading for a meal. But Matt won’t give in. The hunger clears his mind, keeps him sharp—and he needs to be as sharp as possible if he’s going to find out just how Tariq and his band of high school bullies drove his sister, Maya, away.

Matt’s hardworking mom keeps the kitchen crammed with food, but Matt can resist the siren call of casseroles and cookies because he has discovered something: the less he eats the more he seems to have . . . powers. The ability to see things he shouldn’t be able to see. The knack of tuning in to thoughts right out of people’s heads. Maybe even the authority to bend time and space.

A darkly funny, moving story of body image, addiction, friendship, and love, Sam J. Miller’s debut novel will resonate with any reader who’s ever craved the power that comes with self-acceptance."

not all black girls know how to eat: a story of bulimia

by Stephanie Covington Armstrong

Overview

"Stephanie Covington Armstrong does not fit the stereotype of a woman with an eating disorder. She grew up poor and hungry in the inner city. Foster care, sexual abuse, and overwhelming insecurity defined her early years. But the biggest difference is her race: Stephanie is black.

In this moving first-person narrative, Armstrong describes her struggle as a black woman with a disorder consistently portrayed as a white woman’s problem. Trying to escape her selfhatred and her food obsession by never slowing down, Stephanie becomes trapped in a downward spiral. Finally, she can no longer deny that she will die if she doesn’t get help, overcome her shame, and conquer her addiction to using food as a weapon against herself."

CELEBRITIES WHO ADVOCATE

"'I didn’t know if I was going to feel comfortable with talking about body image and talking about the stuff I’ve gone through in terms of how unhealthy that’s been for me — my relationship with food and all that over the years,' she tells Variety. 'But the way that Lana (Wilson, the film’s director) tells the story, it really makes sense. I’m not as articulate as I should be about this topic because there are so many people who could talk about it in a better way. But all I know is my own experience. And my relationship with food was exactly the same psychology that I applied to everything else in my life: If I was given a pat on the head, I registered that as good. If I was given a punishment, I registered that as bad.'"

"From early adolescence Brand was suspected to be bipolar and hyper-manic, though he was only treated for depression. Around the age of 11 he started binge-eating and vomiting. 'It was really unusual in boys, quite embarrassing. But I found it euphoric.'

As an adult, when he was in rehab, the bulimia briefly returned. 'It was clearly about getting out of myself and isolation. Feeling inadequate and unpleasant.'

It didn't help that Brand was a lonely only child, and fat. 'I didn't master the bulimia, obviously.' Seriously, does he feel sorry for the child he was? 'I've realised that I do,' he says. 'Of course I've been through lots of therapy. But I do feel a sense of "you poor little sod". I loved my mum madly, but I had a lot of prohibiting, inhibiting things around. My feeling about my childhood was that it was lonely and difficult.'"

Discover Seasonal Depression

month of december

What is Seasonal Depression?

According to the NIMH

Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD) is a type of depression that comes and goes with the seasons, typically starting in the late fall and early winter and going away during the spring and summer. Depressive episodes linked to the summer can occur, but are much less common than winter episodes of SAD.

General Statistics

National Institute of Psychology Today

-

Seasonal affective disorder is estimated to affect 10 million Americans.

-

Another 10 percent to 20 percent may have mild SAD.

-

SAD is four times more common in women than in men.

-

The age of onset is estimated to be between the age of 18 and 30.

-

Some people experience symptoms severe enough to affect quality of life, and 6 percent require hospitalization.

-

Many people with SAD report at least one close relative with a psychiatric disorder, most frequently a severe depressive disorder (55 percent) or alcohol abuse (34 percent).

Video: Learn About Seasonal Affective Disorder | UPMC

Do you suffer from SAD? Learn more about the signs and symptoms of Seasonal Affective Disorder and how you can cope in the autumn and fall. Read more: https://share.upmc.com/2015/10/how-seasons-change-mood/

ARTICLES ABOUT SAD

When I Realized My Depression Was Seasonal

"It took me several years to realize how much sunlight and the seasons affect my mental health. My first episode of major depression began in late fall and eased in early spring, but at the time, that had no significance. I only saw the situational stressors that caused me to become overwhelmed. Increasing pain in my back and hips had caused me to stop dancing, which was my passion, stress release and creative outlet at the time. The frustration of being held back by pain was compounded by vague diagnoses and unsuccessful treatments. After a while of this, I was forced to confront the fact that the pain was not going away and I wouldn’t be able to dance anytime soon."

Coping With S.A.D. Moments During Holidays With Seasonal Affective Disorder

"It’s that time of year: the time when we’re cooking, cleaning and entertaining more than usual. We’re traveling and shopping, all on top of everything else we tend to do every day without fail. It’s also when our days get shorter and our nights longer. And for some of us, that means our eyes are not twinkling and our dimples are not merry. Instead, it can be hard to be excited about anything. All many of us really want to do is wrap up in a cozy blanket with a cup of tea and a good book."

7 Ways I'm Preparing for Seasonal Affective Disorder This Year

"I was trapped indoors for days at a time — unable to drive anywhere because road conditions were so bad. At one point during the winter even going for a walk on our farm was dangerous because of the snow and ice. By the end of the winter I was definitely depressed. All I wanted to do was lay in bed and sleep all day and I had no motivation to do any of the activities that I usually enjoy."

THE CHEMISTRY

BEHIND

SAD

"

As the days grow darker and colder, many of us occasionally experience the winter doldrums. A small percentage of the US population (about 1 to 10 percent, depending on where you live), however, suffers a more severe form of the blues known as seasonal affective disorder (SAD), with symptoms such as feeling sluggish, agitated, hopeless, overly fatigued and changes in appetite. In the U.S., the prevalence of SAD is linked to how far north you live. The incidence of SAD is nearly 10 percent of the population in New Hampshire, compared to 1.4 percent in Florida.

SAD didn’t become a clinically diagnosed condition until the 1980s, when physician Norman Rosenthal moved from South Africa to the United States and noticed that he felt unproductive during the winter months and started to bounce back come spring. In its most severe cases, SAD symptoms are in line with a major depressive episode, where people are severely incapacitated, unable to function and may even have suicidal thoughts. Collaborating with colleagues at the National Institutes of Health, Rosenthal conducted research on how light exposure affected circadian rhythms and pioneered the concept of light exposure therapy.

An extensive body of scientific research exists today on SAD, yet researchers still can’t definitively explain why this seasonal-related disorder occurs. They have, however, uncovered some clues showing that decreased daylight exposure disrupts circadian rhythm cycles, which in turn impacts levels of key body regulating hormones or neurotransmitters in the brain such as melatonin and serotonin.

A Misaligned Clock

The morning light is truly nature’s alarm clock. Our retinas have special cells called retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) that detect sunlight and send a signal along nerves to a part of the brain known as the suprachiasmatic nucleus, the timekeeper of our circadian rhythms. The early dawn light sets off a chain of events that tell our internal body clock to send signals to the pineal gland, which inhibits the secretion of melatonin, the hormone that prepares your body to sleep.

In the winter, as such light cues become weaker, our body clock becomes misaligned and melatonin secretion continues, tricking our bodies into thinking it’s still night time. Interestingly, some people who are completely blind—lacking the photoreceptors responsible for vision—still retain the special light-detecting cells, and can also experience SAD.

The Serotonin Connection

Another area of research is dedicated to investigating how SAD is linked to depleted levels of serotonin in the brain, a neurotransmitter that regulates mood. The serotonin connection also helps explain why people with SAD often crave more carbohydrate-rich foods in the winter, which are known to cause a spike in these mood-enhancing chemicals. Researchers have yet to show the crucial link of how diminished daylight leads to a drop in serotonin levels.

But they have done brain scan studies to show that people with SAD had higher levels of a serotonin transporter protein (SERT) in the winter compared to healthy individuals. The more SERT a person has in his/her brain, the less the mood-enhancing neurotransmitter is freely available, causing people to more likely to experience symptoms of depression.

Simulating Nature’s Light

One common, non-invasive treatment for SAD is to use a light therapy box, which mimics natural outdoor light, and may help people recalibrate their body clocks and relieve symptoms of SAD. In Sweden, which has long stretches of winter darkness, officials have brought light therapy to their citizens by converting some bus stops into UV light therapy boxes.

We may have coined the term winter blues even before we knew the science behind it, but research is shedding light on how we can keep our mood a bit sunnier even during those long, dark months."

HOW DOES TREATMENT HELP?

"A number of treatments are available for seasonal affective disorder (SAD), including cognitive behavioural therapy, antidepressants and light therapy.

Your GP will recommend the most suitable treatment option for you, based on the nature and severity of your symptoms. This may involve using a combination of treatments to get the best results.

NICE recommendations

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends that SAD should be treated in the same way as other types of depression.

This includes using talking treatments such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) or medication such as antidepressants.

Light therapy is also a popular treatment for SAD, although NICE says it's not clear whether it's effective.

See NICE guidance about the treatment and management of depression in adults.

Things you can try yourself

There are a number of simple things you can try that may help improve your symptoms, including:

-

try to get as much natural sunlight as possible – even a brief lunchtime walk can be beneficial

-

make your work and home environments as light and airy as possible

-

sit near windows when you're indoors

-

take plenty of regular exercise, particularly outdoors and in daylight – read more about exercise for depression

-

eat a healthy, balanced diet

-

if possible, avoid stressful situations and take steps to manage stress

It can also be helpful to talk to your family and friends about SAD, so they understand how your mood changes during the winter. This can help them to support you more effectively.

Psychosocial treatments

Psychosocial treatments focus on both psychological aspects (how your brain functions) and social aspects (how you interact with others).

Cognitive behavioural therapy

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is based on the idea that the way we think and behave affects the way we feel. Changing the way you think about situations and what you do about them can help you feel better.

If you have CBT, you'll have a number of sessions with a specially trained therapist, usually over several weeks or months. Your programme could be:

-

an individual programme of self-help

-

a programme designed for you and your partner (if your depression is affecting your relationship)

-

a group programme that you complete with other people in a similar situation

-

a computer-based CBT programme tailored to your needs and supported by a trained therapist

Read more about CBT.

Counselling and psychodynamic psychotherapy

Counselling is another type of talking therapy that involves talking to a trained counsellor about your worries and problems.

During psychodynamic psychotherapy you discuss how you feel about yourself and others and talk about experiences in your past. The aim of the sessions is to find out whether anything in your past is affecting how you feel today.

It's not clear exactly how effective these 2 therapies are in treating depression.

Read more about psychotherapy.

Antidepressants

Antidepressants are often prescribed to treat depression and are also sometimes used to treat severe cases of SAD, although the evidence to suggest they're effective in treating SAD is limited.

Antidepressants are thought to be most effective if taken at the start of winter before symptoms appear, and continued until spring.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the preferred type of antidepressant for treating SAD. They increase the level of the hormone serotonin in your brain, which can help lift your mood.

If you're prescribed antidepressants, you should be aware that:

-

it can take up to 4 to 6 weeks for the medication to take full effect

-

you should take the medication as prescribed and continue taking it until advised to gradually stop by your doctor

-

some antidepressants have side effects and may interact with other types of medication you're taking

Common side effects of SSRIs include feeling agitated, shaky or anxious, an upset stomach and diarrhoea or constipation. Check the information leaflet that comes with your medication for a full list of possible side effects.

Read more about antidepressants.

Light therapy

Some people with SAD find that light therapy can help improve their mood considerably. This involves sitting by a special lamp called a light box, usually for around 30 minutes to an hour each morning.

Light boxes come in a variety of designs, including desk lamps and wall-mounted fixtures. They produce a very bright light. The intensity of the light is measured in lux – the higher lux, the brighter the light.

Dawn-stimulating alarm clocks, which gradually light up your bedroom as you wake up, may also be useful for some people.

The light produced by the light box simulates the sunlight that's missing during the darker winter months.

It's thought the light may improve SAD by encouraging your brain to reduce the production of melatonin (a hormone that makes you sleepy) and increase the production of serotonin (a hormone that affects your mood).

Who can use light therapy?

Most people can use light therapy safely. The recommended light boxes have filters that remove harmful ultraviolet (UV) rays, so there's no risk of skin or eye damage for most people.

However, exposure to very bright light may not be suitable if you:

-

have an eye condition or eye damage that makes your eyes particularly sensitive to light

-

are taking medication that increases your sensitivity to light, such as certain antibiotics and antipsychotics, or the herbal supplement St. John's Wort

Speak to your GP if you're unsure about the suitability of a particular product.

Trying light therapy

Light boxes aren't usually available on the NHS, so you'll need to buy one yourself if you want to try light therapy.

Before using a light box, you should check the manufacturer's information and instructions regarding:

-

whether the product is suitable for treating SAD

-

the light intensity you should be using

-

the recommended length of time you need to use the light

Make sure that you choose a light box that is medically approved for the treatment of SAD and produced by a fully certified manufacturer.

Does light therapy work?

There's mixed evidence regarding the overall effectiveness of light therapy, but some studies have concluded it is effective, particularly if used first thing in the morning.

It's thought that light therapy is best for producing short-term results. This means it may help relieve your symptoms when they occur, but you might still be affected by SAD next winter.

When light therapy has been found to help, most people noticed an improvement in their symptoms within a week or so.

Side effects of light therapy

It's rare for people using light therapy to have side effects. However, some people may experience:

-

agitation or irritability

-

headaches or eye strain

-

sleeping problems (avoiding light therapy during the evening may help prevent this)

-

tiredness

-

blurred vision

These side effects are usually mild and short-lived, but you should visit your GP if you experience any particularly troublesome side effects while using light therapy."

CELEBRITIES WHO ADVOCATE

"O’Donnell also says she suffers from seasonal affective disorder, often called SAD, which causes her to feel depressed during the fall and winter. 'Like in The Wizard of Oz, the color goes out,' she says. 'That is what happens in depression. Everything gets gray.'

No one should fear the stigma of taking medication for depression, she says: 'It saved my life.'"

Discover Depression

month of october

What is Depression?

According to the American Psychiatric Foundation

Depression (major depressive disorder) is a common and serious medical illness that negatively affects how you feel, the way you think and how you act. Fortunately, it is also treatable. Depression causes feelings of sadness and/or a loss of interest in activities once enjoyed. It can lead to a variety of emotional and physical problems and can decrease a person’s ability to function at work and at home.

General Statistics

National Institute of Mental Health

-

Major depressive disorder affects approximately 17.3 million American adults, or about 7.1% of the U.S. population age 18 and older, in a given year. (National Institute of Mental Health “Major Depression”, 2017)

-

Major depressive disorder is more prevalent in women than in men. (Journal of the American Medical Association, 2003; Jun 18; 289(23): 3095-105)

-

1.9 million children, 3 – 17, have diagnosed depression. (Centers for Disease Control “Data and Statistics on Children’s Mental Health”, 2018)

-

Adults with a depressive disorder or symptoms have a 64 percent greater risk of developing coronary artery disease. (National Institute of Health, Heart disease and depression: A two-way relationship, 2017)

What is depression? - Helen M. Farrell | Ted-Ed

Depression is the leading cause of disability in the world; in the United States, close to ten percent of adults struggle with the disease. But because it’s a mental illness, it can be a lot harder to understand than, say, high cholesterol. Helen M. Farrell examines the symptoms and treatments of depression, and gives some tips for how you might help a friend who is suffering.

ARTICLES ABOUT DEPRESSION

Talking About Depression Is Uncomfortable, but Necessary

Add some info about this item

"We need to break through the uncomfortable barrier in order to really help someone. Being uncomfortable for a few seconds, minutes or hours is worth it if it saves a life. Seems a bit dramatic but it’s true. I was once contemplating my suicide and if it would hurt. However depressed and suicidal I was, I got a message on Facebook from my partner, just asking how I was. That saved my life. She saved my life without even knowing it. The littlest things can keep a person living. Remember that."

The Unexpected Symptoms I Didn't Realize 'Screamed' Depression

Add some info about this item

"One thing that makes depression so complex to understand is the fact that it varies so much from person to person. There are multiple lists you can find online with lots of symptoms of depression. When you get the flu, you might have a fever, sore throat and upset stomach and you will know something is wrong and will probably go into the doctor.

With depression, you could feel more tired than usual, irritable, and feel more down on yourself and may have no idea you’re experiencing depression because the “common” symptoms most people use to recognize depression are suicidal thoughts, loss of appetite, hopelessness, anxiety, emptiness and depressed mood. Therefore, because there’s a wide variety of symptoms and you may not match up with all of them, you could easily dismiss it as a rough patch in your life. Or you may not notice the change at all because it’s not uncommon to forget to pay attention to your mental health."

When I Heard Someone Say Some Depressed People 'Don't Want to Get Better'When I Heard Someone Say Some Depressed People 'Don't Want to Get Better'

Add some info about this item

"The comment was about how some depressed people don’t want to get better because they get used to feeling that way, so they just don’t try. Wow. But for those of us with clinical depression (or anxiety, bipolar disorder, etc.), more often than not we do want to get better. That is why we take our medications and go to therapy. Just like patients get treatment and have follow-up visits with their doctors. The list could go on of conditions that are medical and are, therefore, medically treated.

The general population doesn’t seem to get that it’s one and the same with depression. This to me is just ignorance and misinformation. There is a gap between what people think they know about depression and what depression is really like. I think that gap exists for two reasons: One is, like I mentioned before, ignorance and misinformation. It’s when people believe we’re just having a bad day and need to snap out of it. The second reason is you probably can’t understand depression if you have never experienced true clinical depression."

THE CHEMISTRY

BEHIND

DEPRESSION

"Increasingly sophisticated forms of brain imaging — such as positron emission tomography (PET), single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) — permit a much closer look at the working brain than was possible in the past. An fMRI scan, for example, can track changes that take place when a region of the brain responds during various tasks. A PET or SPECT scan can map the brain by measuring the distribution and density of neurotransmitter receptors in certain areas.

Use of this technology has led to a better understanding of which brain regions regulate mood and how other functions, such as memory, may be affected by depression. Areas that play a significant role in depression are the amygdala, the thalamus, and the hippocampus (see Figure 1).

Research shows that the hippocampus is smaller in some depressed people. For example, in one fMRI study published in The Journal of Neuroscience, investigators studied 24 women who had a history of depression. On average, the hippocampus was 9% to 13% smaller in depressed women compared with those who were not depressed. The more bouts of depression a woman had, the smaller the hippocampus. Stress, which plays a role in depression, may be a key factor here, since experts believe stress can suppress the production of new neurons (nerve cells) in the hippocampus.

Researchers are exploring possible links between sluggish production of new neurons in the hippocampus and low moods. An interesting fact about antidepressants supports this theory. These medications immediately boost the concentration of chemical messengers in the brain (neurotransmitters). Yet people typically don't begin to feel better for several weeks or longer. Experts have long wondered why, if depression were primarily the result of low levels of neurotransmitters, people don't feel better as soon as levels of neurotransmitters increase.

The answer may be that mood only improves as nerves grow and form new connections, a process that takes weeks. In fact, animal studies have shown that antidepressants do spur the growth and enhanced branching of nerve cells in the hippocampus. So, the theory holds, the real value of these medications may be in generating new neurons (a process called neurogenesis), strengthening nerve cell connections, and improving the exchange of information between nerve circuits. If that's the case, depression medications could be developed that specifically promote neurogenesis, with the hope that patients would see quicker results than with current treatments."

Hippocampus: The hippocampus is part of the limbic system and has a central role in processing long-term memory and recollection. Interplay between the hippocampus and the amygdala might account for the adage "once bitten, twice shy." It is this part of the brain that registers fear when you are confronted by a barking, aggressive dog, and the memory of such an experience may make you wary of dogs you come across later in life. The hippocampus is smaller in some depressed people, and research suggests that ongoing exposure to stress hormone impairs the growth of nerve cells in this part of the brain.

HOW DOES TREATMENT HELP?

Amygdala: "The amygdala is part of the limbic system, a group of structures deep in the brain that's associated with emotions such as anger, pleasure, sorrow, fear, and sexual arousal. The amygdala is activated when a person recalls emotionally charged memories, such as a frightening situation. Activity in the amygdala is higher when a person is sad or clinically depressed. This increased activity continues even after recovery from depression."

Thalamus: "The thalamus receives most sensory information and relays it to the appropriate part of the cerebral cortex, which directs high-level functions such as speech, behavioral reactions, movement, thinking, and learning. Some research suggests that bipolar disorder may result from problems in the thalamus, which helps link sensory input to pleasant and unpleasant feelings."

"Living with depression can be difficult, but treatment can help improve your quality of life. Talk to your doctor about possible options.

You may successfully manage symptoms with one form of treatment, or you may find that a combination of treatments works best. It’s common to combine medical treatments and lifestyle therapies, including the following:

Medications

Your doctor may prescribe antidepressants, antianxiety, or antipsychotic medications.

Each type of medication that’s used to treat depression has benefits and potential risks.

Psychotherapy

Speaking with a therapist can help you learn skills to cope with negative feelings. You may also benefit from family or group therapy sessions.

Light Therapy

Exposure to doses of white light can help regulate mood and improve symptoms of depression. This therapy is commonly used in seasonal affective disorder (which is now called major depressive disorder with seasonal pattern).

Alternative Therapies

Ask your doctor about acupuncture or meditation. Some herbal supplements are also used to treat depression, like St. John’s wort, SAMe, and fish oil.

Talk with your doctor before taking a supplement or combining a supplement with prescription medication because some supplements can react with certain medications. Some supplements may also worsen depression or reduce the effectiveness of medication.

Exercise

Aim for 30 minutes of physical activity three to five days a week. Exercise can increase your body’s production of endorphins, which are hormones that improve your mood.

Avoid Alcohol and Drugs

Drinking or using drugs may make you feel better for a little bit. But in the long run, these substances can make depression and anxiety symptoms worse.

Learn How To Say No

Feeling overwhelmed can worsen anxiety and depression symptoms. Setting boundaries in your professional and personal life can help you feel better.

Take Care of Yourself

You can also improve symptoms of depression by taking care of yourself. This includes getting plenty of sleep, eating a healthy diet, avoiding negative people, and participating in enjoyable activities.

Sometimes depression doesn’t respond to medication. Your doctor may recommend other treatment options if your symptoms don’t improve.

These include electroconvulsive therapy, or transcranial magnetic stimulation to treat depression and improve your mood."

MY EXPERIENCE

WITH DEPRESSION

TRIGGER WARNING: Self-harm, depression, suicidal idealization

Two years ago, in 2017, I almost gave up. I had panic attacks everyday in school and wound up in the big all gender bathroom stall every lunch, crying mascara down my cheeks until all that was left was trails of black. Some people would hear me crying but I felt so alone that I tried hard to muster my crying because I knew that people called me dramatic an someone who craved attention. I'm sick and tired of that stigma. People could come and ask me to come out even though they didn't often didn't know who I was. They saw me run to the bathroom crying and they would tell me to come out and hug me. Those hugs meant a lot even though sometimes they were uncomfortable.

Sometimes you would cry so hard your lungs started shuddering uncontrollably and it's difficult to get enough oxygen to your brain and the rest of your body and it escalates your panic attack that much more. I think this is the way that it goes for a lot of people, so that you can't remember exactly how fast the days went and how strong your feelings were but all your remember was numbness. That's what it felt like for me. Time felt slow. Everything took so much effort. I stopped enjoying the thing that I loved and felt out of place in the places I used to call home.

Depression is something that fucks with every aspect of your life. It's not just a figment of the imagination. It's not just a tactic people use to get attention. It's an illness which is caused by chemical changes in the brain. You've heard in biology that our brain chemistry can be altered by our surroundings, and it's very real.